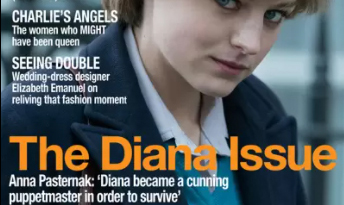

Anna Pasternak on Diana and the secret letters which informed her explosive 1994 biography

Until now, I haven’t been a fan of The Crown due to its historically inaccurate howlers. Prince Philip’s mother, Princess Alice, giving an interview to The Guardian is, for example, too good to be true. However, the new season’s portrayal of Charles and Diana’s unravelling marriage is grimly compelling. Emma Corrin nails Diana’s transformation from Shy Di to wounded manipulator. She’s a gangly aristocratic tripwire waiting to detonate, her vulnerability laced with petulant fury, while Josh O’Connor is the spit of Eeyorish Charles, trapped in despair that only husky Camilla Parker Bowles (Emerald Fennell) can alleviate.

What struck me as I watched this, 27 years after writing Princess in Love – which detailed Diana’s affair with Captain James Hewitt – was how sorry I now feel for Diana, Charles and Camilla. Each of the trio suffered at the hands of an unrelenting monarchy. Then, of course, I was firmly Team Diana, castigating Charles and Camilla as selfish bullies. Hewitt had allowed me to read the 64 air-mail ‘blueys’ that Diana had sent him at the height of their affair, while he was serving in the Gulf War. He wanted me to understand how deep their love went. I remember burning with injustice as I read them, fiercely defensive of our adored, lonely princess. Every day she wrote to Hewitt – signing the letters ‘Julia’ – about how snubbed she felt by the palace, and her frenzied anger over Camilla. That she had married her prince, but was unable to capture his heart, drove her to distraction. And destruction.

When Princess in Love was published in 1994, I was a 26-year-old ingénue. I had met Hewitt socially in 1993. A charming Sloane, he was reportedly discharged from the army due to rumours of his close correspondence with Diana. I wrote an anodyne series for the Daily Express, detailing St Diana doing the washing up at Hewitt’s mother’s cottage. The series lasted a week, and I went to Hewitt’s Devon home to interview him for it. He told me he was only speaking to me because Diana asked him to – though the series never hinted at an affair, it just showed the pair as good friends. Diana was in constant contact with Hewitt during this time. He told me that she thanked him on the phone for ‘talking, as you know I can’t. At least people will know the truth.’ Which presumably is exactly what she said to Andrew Morton when she laid bare the horrors of her royal life for Diana: Her True Story, published in 1992. Well, everything except her affair with the dashing captain, who taught William and Harry to ride.

Diana became a cunning puppetmaster in order to survive. I was unaware of her guile. Worried Morton would reveal the affair in his second book, she wanted to control the narrative. She insisted to Hewitt that if the world could see that their love was genuine, and could understand why she turned to him in the face of Charles’s rejection, they would not condemn her. The brief I got from Hewitt was to write a love story in four weeks, to be published ahead of Morton’s offering. I knew nothing of love but wrote my best gushing account, wholly flattering to the wronged princess. The book was immediately dismissed as romantic nonsense. Worse, it was apparently my ‘romantic fantasy’. Quite why I would fantasise about this escapes me to this day. I regret that I used so many adjectives – as Fay Weldon wrote: ‘Why is everyone being so mean about this book? There is nothing wrong with it apart from a few soapy adjectives’ – but I stand by my assertion that the Royal Family should have been grateful to Hewitt. He loved and listened to Diana when they wouldn’t. At her most unstable, in the grip of bulimia, which The Crown depicts in unflinching hunched-over-the-lavatory-bowl detail, he was her mainstay.

In 1994, no one believed that the royal marriage was as bad as The Crown illustrates. I was flayed alive in the press. At a party that autumn, the fashion designer Ben de Lisi furiously confronted me: ‘Thanks to you, Princess Diana cancelled her appointment with me on the day your book was published because she was so hurt and shocked.’ ‘How strange,’ I retorted, ‘because she was the third person to know the publication date.’ A year later, Diana confessed to her affair in the controversial Panorama interview and suddenly everything I had written was confirmed as true. Charles and Diana divorced the following year.

Princess in Love continues to navigate choppy waters. In October, when Robert Lacey’s book Battle of Brothers was serialised in the Daily Mail, I was appalled to read: ‘William and Harry were informed by Anna Pasternak’s book that Uncle James had made love to their mother in a Highgrove lavatory while they were on the other side of the door.’ This unedifying scene was completely fabricated. Why would I write such a damning view of Diana when I was sympathetic to her, describing the devoted mother she was? Diana’s friend and astrologer Debbie Frank emailed: ‘I am horrified by Robert Lacey’s serialisation. It is brutal towards Diana and you. I can’t bear such unfairness for his own aggrandisement. A very hostile attack.’

When I alerted the Mail to this distortion, they apologised and made amends. Lacey’s publisher was less contrite. She asserted that Lacey’s ‘research team’ had found an article in People magazine, in 1994, that screamed: ‘They did it in the bathroom!’ Her reasoning was that if I didn’t complain to People back then, why would I do so now? She made the even more spurious claim that because I wrote of Diana and Hewitt discreetly sharing a four-poster at Highgrove, this exonerated Lacey’s grubby Highgrove loo claim. Yet I specifically wrote in Princess in Love: ‘During their days at Highgrove they were careful not to let William or Harry have so much of a glimpse of their secret.’

No wonder The Crown has so many inaccuracies: Robert Lacey is their historical consultant. Confusingly, he believes: ‘There are two sorts of truth. There’s historical truth and then then there’s the larger truth about the past.’ There’s also fabrication. If only Diana’s true story was fictional and not the factual tragedy that rocked the crown.

The fourth season of The Crown arrives on Netflix on Sunday 15 November