No happy endings

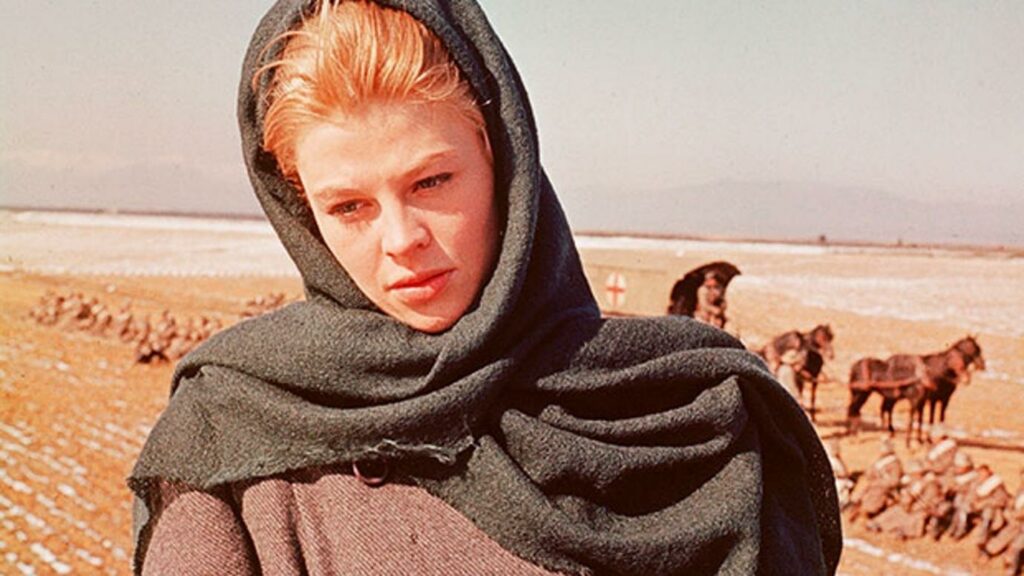

The beautiful, widowed Olga Ivinskaya, exiled to the gulag for her association with Boris Pasternak, was as tragic a figure as her fictional counterpart, according to Pasternak’s great niece

Between agreeing to review this book and receiving it, I got worried. Like many, I adore Doctor Zhivago with its tragic love story between the eponymous doctor-poet and the beautiful Lara, set in post-revolutionary Russia. When in Moscow, I followed the trail of literary pilgrims to Boris Pasternak’s dacha in the writers’ village of Peredelkino. I also had fond memories of Julie Christie and Omar Sharif in David Lean’s epic 1965 film; never underestimate the enhancing effect on romance of fur hats, sparkling snow and long-distance trains. Anna Pasternak, the writer’s great niece, is a journalist and Daily Mail columnist who made her name with Princess in Love. This 1995 collaboration with ‘love rat’ (as the tabloids dubbed him) James Hewitt detailed his affair with Princess Diana and was followed by the 2008 novel Daisy Dooley Does Divorce.

So it was with trepidation that I opened Lara. How would the author move from love rat to literary muse? And was Olga Ivinskaya, the supposed model for the character of Lara, anything special? Christopher Barnes, Pasternak’s biographer, dismissed (‘slut-shamed’?) Olga as an ‘ambitious and manipulative’ adventuress who fabricated a narrative, placing

herself centre stage, and who probably invented her pregnancy by Pasternak and the miscarriage while imprisoned in the terrifying Lubyanka. In fact, he claims, it was just a ‘saccharine flirtation’ with the great man, who admitted a ‘sweet tooth for female company’. The New York Times also summed up a clique of Russian scholars and intellectuals’ opinion of Olga as ‘Lara-Shmara’, suggesting that she had cooperated with the KGB. Unsurprisingly, the Pasternak family demonised Olga and tried to write her out of history.

What a pleasurable surprise, then, to find that Lara is a marvellously interesting book in which the author makes a convincing case for Olga as Pasternak’s great love, literary support, and at least a partial model for the heroine of Doctor Zhivago.

When Boris met Olga, it was 1946 and she was working at the Moscow offices of the literary magazine Novy Mir (New World). She was a 34-year-old, twice-widowed mother of two with blonde hair, sad blue eyes and a long-standing crush on Pasternak. He was 56 and a celebrated poet in the Russian way; lives were willingly risked by reciting perilous poems around kitchen tables and fans of lyric verse filled large auditoriums. If Pasternak paused during a recital, ‘the entire crowd continued to roar the next line of his verse back at him, just as they do at pop concerts today’. Stalin’s henchmen kept confirming that the pen is mightier than the sword by arresting and executing poets, though it was Stalin’s fondness for Pasternak’s translations of Georgian poetry that probably saved the writer from the fate of so many of his literary contemporaries.

The pair were soon embroiled in an affair that was to last until his death in 1960. It was anguished, obsessive and blissful, with ideal elements for a good story: a tormented genius; secret police; and not just a wife, but a whole totalitarian state obstructing the course of true love. Pasternak’s friend the poet Marina Tsvetaeva said, ‘Boris is incapable of a happy love. For him to love means to be tortured.’ This was the man who, when married for the first time, persuaded his best friend’s wife to run off with him by swallowing a bottle of iodine in a failed suicide attempt. He felt understandable guilt towards this second spouse when he fell for Olga, but it didn’t stop him leading everyone a merry dance. He ruthlessly skipped between what became his two households, ignored his children, demanded quiet routines for his writing and agonised neurotically about his own psycho-somatic problems. He also refused to ‘make an honest woman’ out of Olga, even after she’d been sent to the gulag for her association with him; she would have been protected by sharing his surname. He was just as stubborn with Khrushchev’s regime when it tried to suppress his great 1957 novel for its criticism of the revolution, though the pressure was so great that he declined the Nobel Prize. First published in Italy and then around the world, it wasn’t until 1988 that Doctor Zhivago came out in Russia.

Anna Pasternak observes her great-uncle’s faults with a clear eye, but like her, one can’t help warming to his passionate nature, his genuine struggles with morality and the seriousness with which he wrote about the country he loved so much he refused to leave even when his life was in danger. The many quotes from his writing are reminders of how brilliant he was. Like the fictional Yuri and Lara, Boris and Olga’s forbidden love was defined by Soviet terrors and deprivations. There are no happy endings in either version, but both are fascinating tales.