The other zhivago affair

Anna Pasternak rights an ancestral wrong, but can’t help playing matchmaker . . .

By Elizabeth Kiem Jan 24, 2017

Anna Pasternak concedes it proudly: “I’m a hopeless romantic. It’s in the genes.”

Pasternak is, yes, related to Boris, the rock-star poet of 20th century Russia.

She’s also a writer drawn to messy affairs of the heart — Lady Diana’s, controversially; her own, transformatively; and most recently, that of her celebrated great-uncle.

What she is not is a scholar, nor a snob, nor a watchdog of her family name. A look at her publications suggests as much. A chat over tea confirms it.

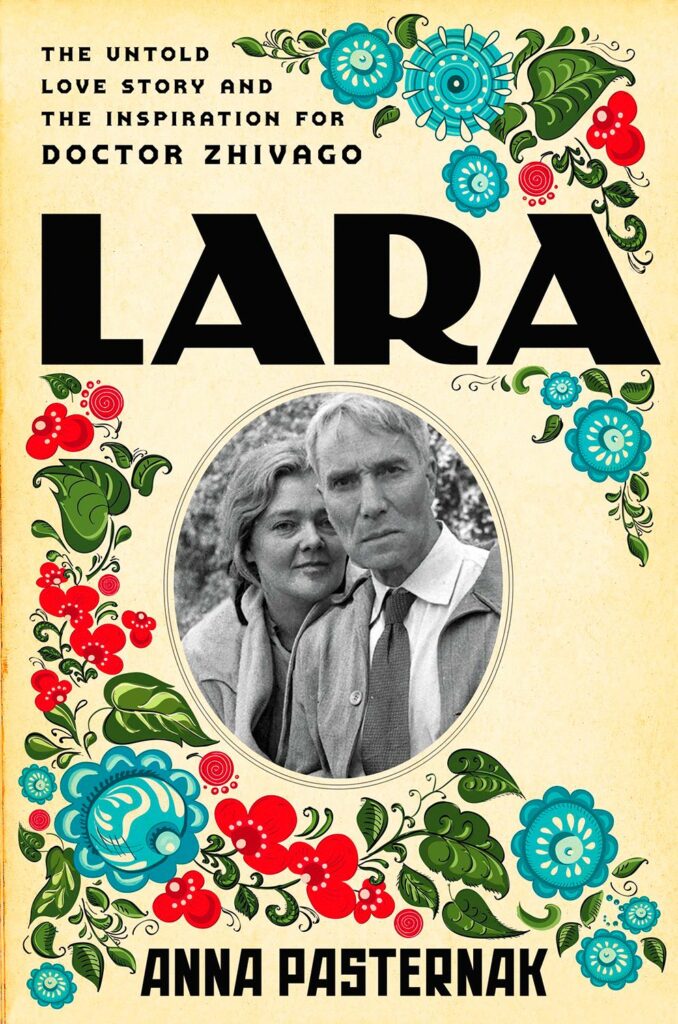

“I was underestimated the whole way through,” she tells me about her long quest to write Lara: the Untold Love Story that Inspired Doctor Zhivago. “There was this constant sense of: did I really know my stuff?”

Twenty years after first broaching the subject of Boris Pasternak’s muse and a month after the release of Lara in the UK to warm reviews, the anxiety surrounding the reception of this “untold story” lingers. “I wasn’t intellectually ready yet…” Pasternak explains three times before our tea arrives. When she does, there’s a hint of that younger woman in her handsome face. She has her great-uncle’s dark skin, strong chin, and expressive eyes.

Her first skeptic was Boris’s sister Josephine, an émigré of pre-Revolutionary Russia and an eminent fixture of the Oxford literati. Josephine was accustomed to the regular attentions of foreign academics; her own granddaughter had to make an appointment to consult her. The ensuing interview, a “vituperative denunciation,” of “that woman,” gave Anna material for her first article in a national paper. But it made the budding journalist wary of tackling the larger story of Olga Ivinskaya, the woman whose relationship with Boris Pasternak has been underestimated longer than Anna Pasternak has been alive.

“I knew then this was a destiny project for me and I was the one to tell it. But I wasn’t …” Pasternak sips her tea and muses on emotional maturity.

A decade after her grandmother’s insistence that elevating her revered brother’s mistress to muse was a “mistaken idea,” Anna Pasternak went back to the story of the real-life Lara. By then her long-suffering subject was gone: having outlived her lover and suffered significant political and personal persecution on his behalf, Olga Ivinskaya died in Moscow in 1995. Her daughter Irina, however, was alive and living in Paris. It took Pasternak five years to gain an audience.

“It was the hardest interview of my career,” she recalls.

Unlike Anna and other blood-relations who were born and raised in the West and never met him personally, Irina Emilianova came of age in the company of Boris Pasternak. As a teenager, she consoled the tortured poet over the arrest of her mother. After his death, she joined her mother in the gulag for a second sentence — punishment for the success of the renegade manuscript they had helped smuggle to the West. Into her seventies, Irina still idolized the man who put the fate of Doctor Zhivago before the safety of her mother; and she still resented the unyielding antagonism of the extended Pasternak family towards the woman who had paid the highest price for the novel’s fame.

“Irina immediately wrote me off as an intellectual lightweight,” says Pasternak, describing a trial by fire during which she was subjected to a historical and literary interrogation in four languages and then shown the door. She might have had gotten her interview, but she had gained no respect and very little trust.

“I realized that I would really have to up my game. I couldn’t afford to get anything wrong.”

Pasternak squints into the sunlight and I feel for her. A hopeless romantic, genetically disposed to drama but tied by birthright to excellence.

Anna Pasternak was taught that talking about her famous family was as gauche as talking about money. “We were brought up to make our own name,” she says.

Her father made his name as a renowned scientist. Her aunt, as an esteemed translator. Her grandmother was a respected philosopher. Anna chose to make her name with a tabloid account of Princess Diana and a polo-playing cavalry officer.

She followed this best-selling critical flop by writing solid chic-lit fare “for every national paper.” Inviting public scrutiny of her personal life, Pasternak chronicled her divorce in a weekly column and ruminated in print over her ambivalence towards motherhood. Her well-documented and hysteria-tinged quest for happiness ended about four years ago, when Pasternak married her psychotherapist. They have since written a book on spiritual quests, soul-mates and marital honesty.

I proffer this reductive CV not to add to the intellectual skepticism that dogs the author of Princess in Love, but to repeat what she already knows and is the first to admit: Anna Pasternak is neither a snob nor a scholar.

“I’m from a family of academics!” she exclaims, before despairing of the intellectual’s “fixation on fact.” Having read all of the leading biographies of Boris Pasternak, the seasoned social-set columnist and Women’s Hour guest concludes: “they are all interested in the literature and styles of writing, which I’m not interested in. I’m interested in the love story.”

There is a hole there, between the vow to be rigorous and the flirtation of poking fun. The thud of something dropped in that gap echoes, but I find myself nodding emphatically. I’m nodding because I, too, am interested in the love story. I too, can’t recite a line of Boris Pasternak’s poetry but prefer to collect photos of him along with incomparable descriptions like that of Maria Tsvetaeva: “He looks at the same time like an Arab and like his horse.”

I’m nodding because I’m fascinated to learn that Anna Pasternak has approached her famous ancestor with the same outsider’s interest as, well, anybody. And she has the honesty to admit that she has had to “up her game” to do so.

Boris Pasternak and Olga Ivinskaya met in 1946. Their love was instant, unconditional, and a moral dilemma for Pasternak, who could not bring himself to leave his wife and family for the younger woman.

That, of course, is the dilemma of Yuri Zhivago.

The question of whether “Lara” is Olga Ivinskaya in spirit or incarnate is one best answered with disclaimers. As a character, Lara predates Olga, and aspects of her younger character (like the abuse of a predatory family friend) tie her more closely to Pasternak’s wife, Zinaida, than to the twice-widowed Olga.

Boris was less equivocating. “Lara lives,” he would tell the visitors to Peredelkino who defied the state’s disfavor to pay tribute to the man who had turned down the Nobel Prize. “Lara lives,” he would say, with a gesture across the lake to Olga’s cottage. “Go and meet her.” He once told an English journalist: “The Lara of my late years is inscribed on my heart in her blood and in her imprisonment.”

Their relationship lasted fifteen years — until Pasternak’s death. It survived not just the familiarity of years, but also the endless histrionics and self-absorption of the poet at his most tormented. Most astonishing of all, it survived Ivinskaya’s three years in the gulag, during which Pasternak did little to nothing to secure her freedom, and even went so far as to see the silver lining in the personal torment he felt at her arrest. “It will make my work deeper.”

Theirs was a open secret, an affair that has been hiding in plain sight behind the better-known “Zhivago affair ” — the one involving smuggled manuscripts, covert translations, the CIA, and the Nobel Prize. Lara is the Zhivago affair for romantics, and it is, as its author had hoped, a “cracking good read.”

But here’s the thing — it is not, as Pasternak’s subtitle claims, “untold.”

Do I want to split hairs over a subtitle that almost certainly was suggested by Pasternak’s publicist?

Yes and no.

Yes because when Pasternak pleads, self-deprecatingly, that she couldn’t possibly have managed the onus of permissions and so, instead, successfully (and perhaps unprecedentedly) passed the job of securing citation rights onto her publisher, I think of the coy suggestion in the book’s less-than-exhaustive bibliography that “readers will be able to trace … references without undue trouble.”

She’s right; a short consultation with Olga Ivinskaya’s 1978 memoir, A Captive in Time, confirms that many of Pasternak’s passages — her account of Boris and Olga’s initial meeting and the early years of their affair; her retelling of their countless squabbles, ultimatums and reconciliations; her narrative of Olga’s KGB interrogation, the postcards she received from Boris in prison” — all of this material is drawn, sometimes verbatim, from Ivinskaya’s own published account.

So — yes. I do feel compelled to split hairs, and I do so over our second pot of tea. Lara, I suggest, is not so-much the untold story as the unbelieved story.

“Well that’s just it. She was given short-shrift too,” replies Pasternak. “She wasn’t taken seriously.”

Ivinskaya was a woman who had no reason to doubt her emotional maturity nor her intellectual readiness to tell her story. But instead of being recognized as the unsung heroine after Pasternak’s death, she spent the rest of her life hounded by her relationship. She was harassed not just by Soviet officials intent on making her pay for Pasternak’s crimes, but also by Pasternak’s family in the West, who continued to regard their golden boy’s long-suffering mistress as a charlatan and adventuress.

This is the family from which Anna Pasternak hails, and from whom she is now meeting “frank astonishment,” that she has pulled off a credible piece of nonfiction. Lara, is not original or groundbreaking or even an investigatory work. It is, more importantly, a vindication.

So — no, I don’t want to split hairs. Because though Pasternak is not telling an “untold story,” she is telling an unpopular story. And she is about to make it very popular indeed.

Our time is up. Even as she confesses that it is perhaps only now, at this very moment, that she is fully appreciating the fact that she has righted an ancestral wrong, Anna Pasternak is waving to a woman entering the café. It is her next appointment, Liz Turbridge, producer of Downton Abbey, who is now developing Lara for television adaptation.

Pasternak’s self-doubt is gone. Her antipathy to snobbery, back in the driver seat. She is enthusiastic, confident. She’s going to make something people are going to love. “Sure — print it!” she encourages me after revealing her dream cast. (Hey, Daniel Day Lewis, how’s your Russian accent?)

As I leave Pasternak and her producer to spin more romance from Zhivago, I am thinking about the next chapter of the whole Zhivago affair. I am thinking not of Boris nor Anna … but of another Pasternak entirely. I am thinking of Charles Pasternak, Boris’s nephew and Anna’s father.

Somewhere midway in our conversation, Anna had told me the story of how after the initial, trying interview with Irina Emilianova, she had returned to Paris with Charles in tow.

“My father looks quite like Boris,” she explained. “And when Irina saw him, she just opened up. He cat-nipped her.”

Charles Pasternak, she went on to reveal, bore more than a strong physical resemblance to his uncle. He shared his weaknesses as well. “Exactly the same capacity for intellectual brilliance and stunning naiveté and stupidity,” she clarified. And don’t even get her started on the selfish vanity that prevented Boris Pasternak from summoning the love of his life to his deathbed. “He didn’t want Olga to see him without his false teeth! It’s a Pasternakian trait! My father is obsessed with his appearance.”

But while Boris’s self-absorption proved to be the most disheartening revelation in the process of researching the great-uncle she never met, Pasternak says she has forgiven him. “I realized that I knew this man. I understood his motivation.”

It’s only when I am back at my computer, doing my own research, that I come across a piece Pasternak wrote for the Evening Standard thirteen years ago. Titled “When I didn’t speak to Dad,” it is the story of Charles Pasternak’s infidelity.

In the piece, she writes that her father’s reluctance to give up the other woman spelled the end of her parents’ marriage. Anna picked sides and didn’t speak to her father for a decade. During that time, she writes, I got a perverse pleasure from writing tabloid articles that I knew my father considered beneath me [and] a blatant trashing of the illustrious Pasternak surname.

Anna Pasternak didn’t tell me that story over tea. Instead she told me that, although she come to accept Boris Pasternak’s many faults, she still had trouble forgiving what she saw as his greatest moral transgression: his failure to give Olga Ivinskaya the one thing that might have protected her from the gulag — the Pasternak surname. She told me that it had occurred to her, as she watched the prickly daughter of Olga Ivinskaya, at aged seventy-something, “blossom” in the company of Boris Pasternak’s handsome eighty-year-old nephew, that “if Irina and Charles were to marry …”

That’s the thing about certain Pasternaks. Incurable romantics. It’s in the genes.